Drawing Like a Mexican the Childrens National Art Program Mexico

Born and raised in Mexico, Sabrina Meder studied at the Lycée Français of Mexico and went on to pursue an undergraduate degree in modern French literature in Paris, France.

Born and raised in Mexico, Sabrina Meder studied at the Lycée Français of Mexico and went on to pursue an undergraduate degree in modern French literature in Paris, France.

Passionate nearly literature and the arts, Meder took an internship with René Jeanne, a master typographer and print-maker based in Paris. Thanks to a scholarship from the Société d'Encouragement aux Métiers de 50'Art, she was able to produce numerous books, assembling lead-type works of both poetry and engraving. At the end of her internship, she returned to United mexican states, where she hoped to use the ability of art, creativity and imagination to aid street children by rendering them and their lives—particularly the extreme poverty that threatens to stunt their potential—more visible to the world.

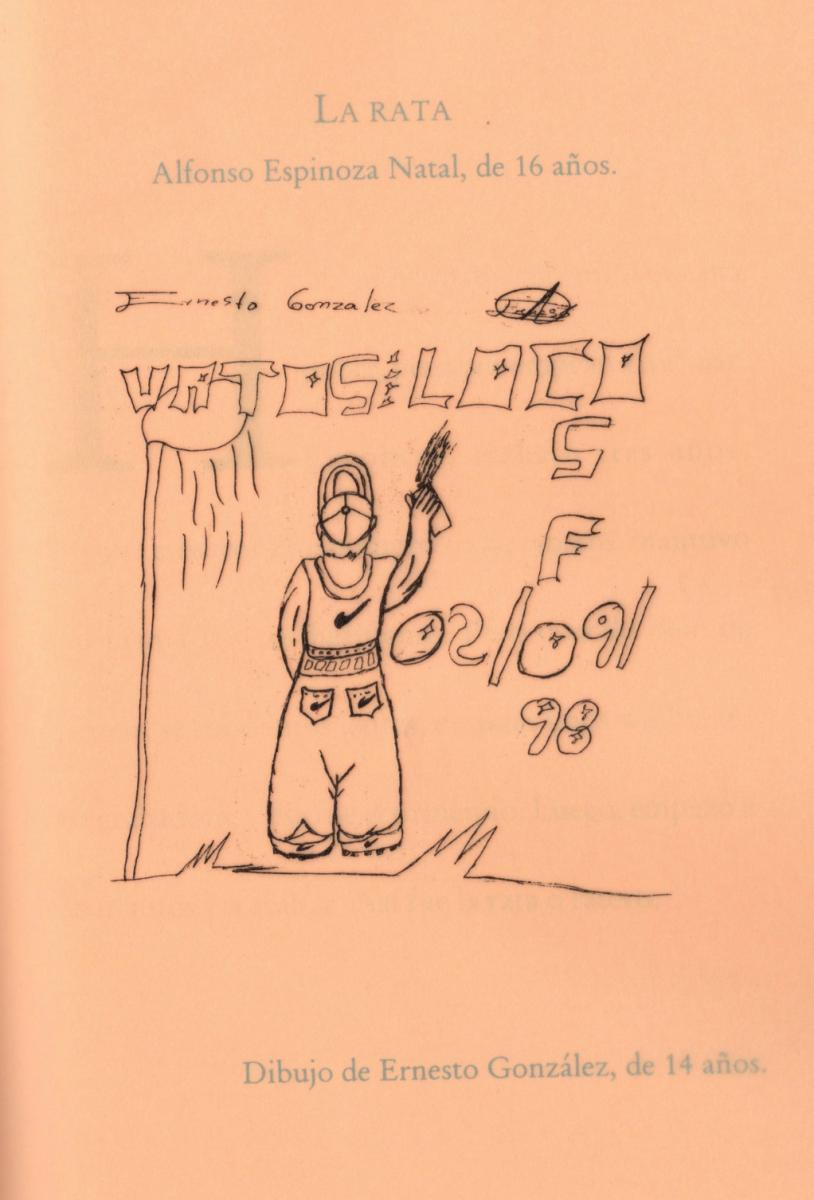

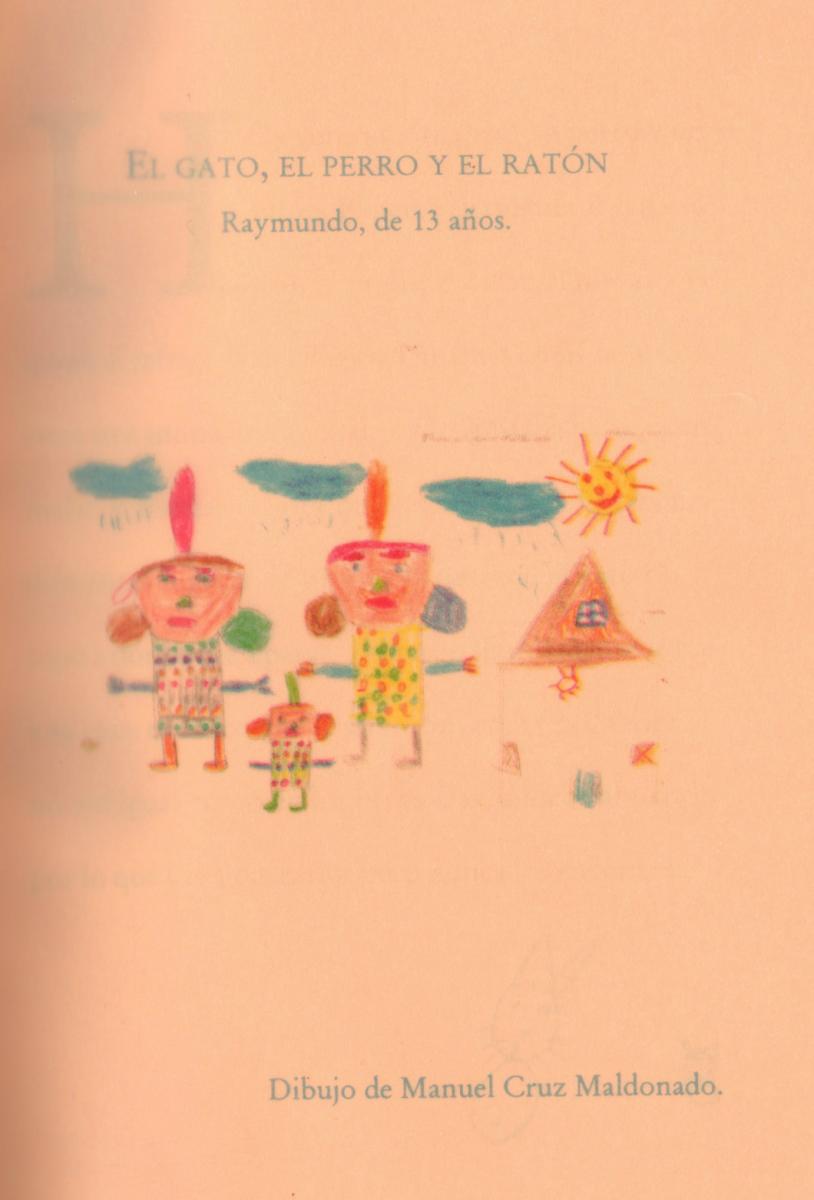

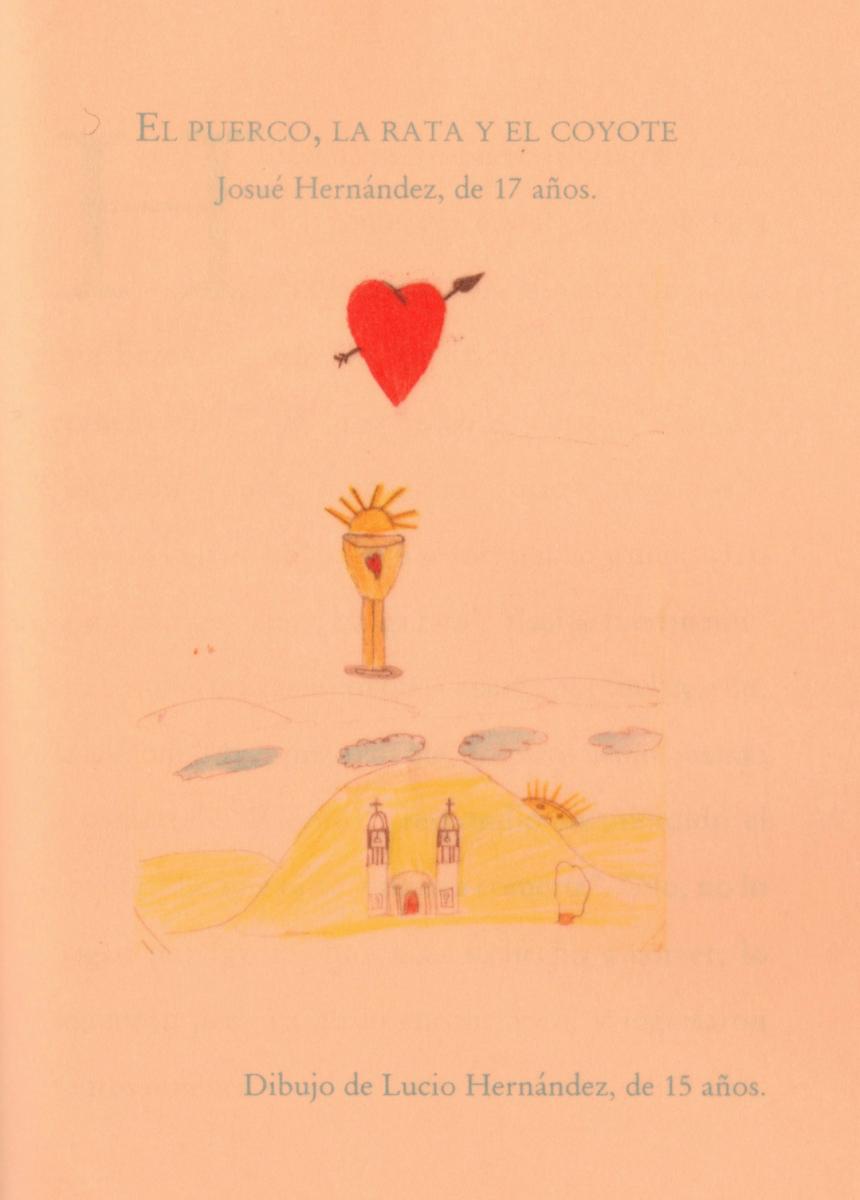

Meder held creativity workshops at Casa Alianza, a transitional habitation for street children, and was stunned by the art produced by the residents: brilliant and eloquent representations of each child's tragic feel of social injustice and poverty. In 1999, she submitted a selection of the children'southward writings and drawings to Mexico'southward annual National Fund for Culture and the Arts competition—the choice concluded upwards winning commencement prize.

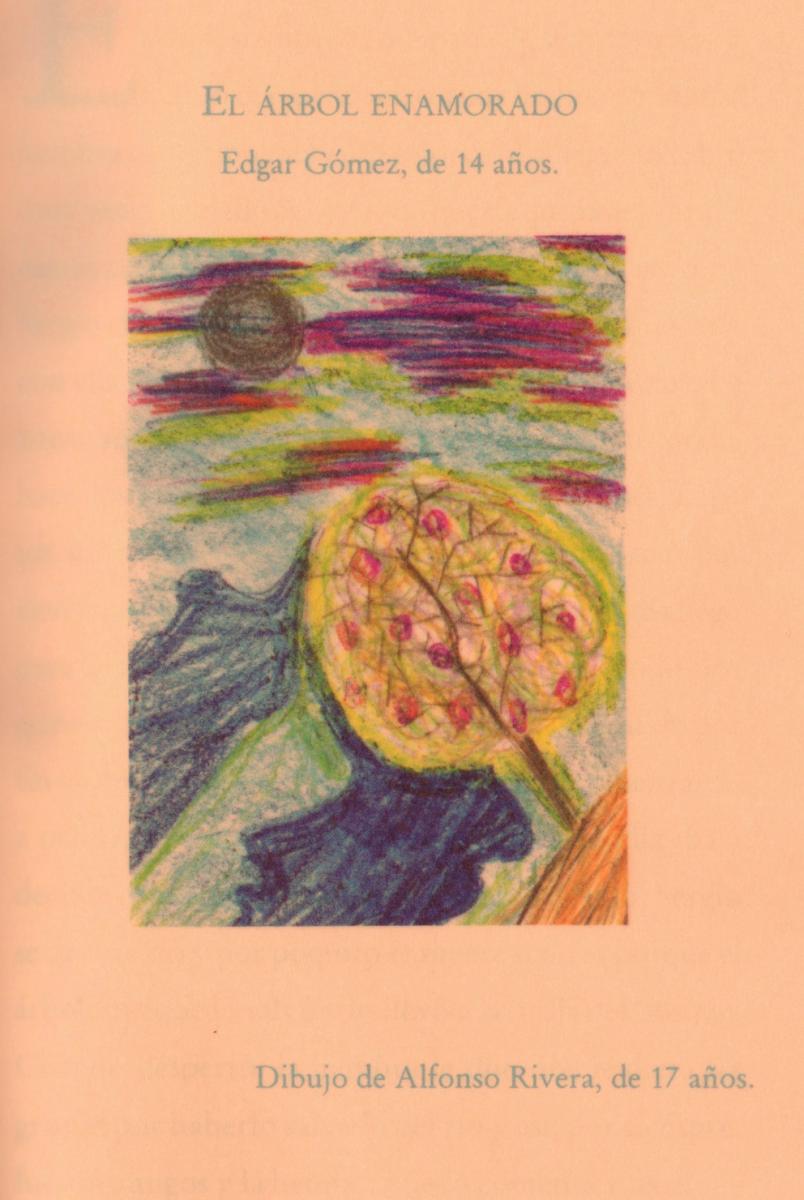

In 2000, Meder published the street children'south artwork in a book, La Vocacion de las Vocales (The Vocation of Vowels). Vowels, Meder says, are the only letters of the alphabet that practice not cause an obstruction of the airway when pronounced. Likewise, her work is intended to help street children to express themselves freely, without obstruction. As readers pore over the book'due south colorful pages, they become immersed in the symbolic art and the complex—and also often overlooked—perspectives of children who have been forced to seek refuge in the streets, living under harsh conditions, becoming excluded from the rest of society.

In 2000, Meder published the street children'south artwork in a book, La Vocacion de las Vocales (The Vocation of Vowels). Vowels, Meder says, are the only letters of the alphabet that practice not cause an obstruction of the airway when pronounced. Likewise, her work is intended to help street children to express themselves freely, without obstruction. As readers pore over the book'due south colorful pages, they become immersed in the symbolic art and the complex—and also often overlooked—perspectives of children who have been forced to seek refuge in the streets, living under harsh conditions, becoming excluded from the rest of society.

Later on working at Casa Alianza, Meder taught French in language centers at various Mexican universities, including Tecnológico de Monterrey and the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de United mexican states (UNAM). Meanwhile, she dedicated her free time to translating William Luret'due south historical novel L'homme de Porquerolles for the Alejo Peralta Foundation, a Mexico-based NGO that promotes educational and cultural activities aimed at encouraging solidarity with marginalized groups throughout United mexican states and ending their social exclusion.

Groovy to develop her artistic skills further, Meder after returned to France, where she familiarized herself with the technique of mono-typing and held several exhibitions of her work (in partnership with a local art association) throughout the French municipality of Seine-et-Marne. During this time, she also kept a blog featuring her personal writings.

Today, still passionate virtually helping children, Meder works every bit an administrative assistant in an organisation that offers fine art and music therapy to autistic children and children with Down's syndrome.

Women's WorldWide Web interviews Sabrina Meder and asks her about her inspiring efforts to empower street children, giving them a voice in society and helping them to exercise their human correct to alive in rubber and dignity, earning the chapters to pursue happier and healthier lives.

W4: What inspired you to create a compilation of street children's writings and drawings?

Sabrina Meder: Information technology was when I returned to Mexico to study literature that an acquaintance talked to me about Casa Alianza, an NGO in Latin America providing care for underprivileged children. I was going through a depression period in my life, suffering from low, and working with the children at Casa Alianza helped requite me back my passion for life. Hither were people living in far worse situations than mine. It actually helped me gain perspective. I grew fond of the children and I besides felt useful—it was a deeply satisfying feel.

Sabrina Meder: Information technology was when I returned to Mexico to study literature that an acquaintance talked to me about Casa Alianza, an NGO in Latin America providing care for underprivileged children. I was going through a depression period in my life, suffering from low, and working with the children at Casa Alianza helped requite me back my passion for life. Hither were people living in far worse situations than mine. It actually helped me gain perspective. I grew fond of the children and I besides felt useful—it was a deeply satisfying feel.

I spent three months with street children in the transitional dwelling, conducting writing and drawing workshops with them when they weren't at schoolhouse. Their writing and artwork were extremely impressive! I was inspired to compile their work and submit it to a competition in the hope of earning enough money to publish a volume.

W4: You say you spent fourth dimension in a "transitional home" for children. Could y'all please explain the role of a transitional home?

Sabrina Meder: At Casa Alianza, in that location are three stages. The beginning phase is the recruitment phase, when we see and talk with children to endeavour to help them to leave the streets and move into the dwelling house. There tend to be 100 to 150 children in the recruitment phase at any given time.

A counselor's office is to help the children to leave life on the streets. Information technology has to be each child'southward option to bring together the home. In many cases, children prefer to remain on the streets, fearing that life in a care home volition be likewise restrictive. Drug use, for example, is prohibited at Casa Alianza. For many street children, life on the streets is synonymous with freedom. As street educators and counselors, our role is to go into the streets to meet and talk with the children and admit new children into the home. We get in pairs to areas frequented by street children. We also go to bus stops, particularly looking for rural children who are new to the city, and so that nosotros tin can talk with them before they start using drugs. Many children are victims of violence and end up in infirmary, and so we as well wait for children in hospitals. Tragically, there are occasions when we find deceased children, for whom nosotros organize funerals.

When a child engages with us and expresses a wish to get out the streets, we enter the 2d stage. We select xx-25 children who will exist given shelter in a transitional domicile and will be reintroduced to schoolhouse.

When a child engages with us and expresses a wish to get out the streets, we enter the 2d stage. We select xx-25 children who will exist given shelter in a transitional domicile and will be reintroduced to schoolhouse.

In the home, each child is cared for by a alive-in counselor, a social worker and a psychologist. In that location are ordinarily two or three counselors per domicile. Where I was working, there were three counselors and a director. Personnel at the dwelling house have 5 hours off each solar day. In total, the counselors take approximately 24 hours off a week.

The dwelling is very well-maintained—clean and well-organized. The rooms are spacious: each room accommodates three or four children. The children help with the household tasks; they exercise their laundry, either in the washing auto or by hand. Nosotros take a cook, and the general atmosphere is very pleasant. In that location are lots of activities: nosotros play football game, we draw, read, tell stories. The objective is to provide a nurturing and stimulating environment for the children and give them a sense of belonging.

The home offers a structured daily rhythm: when I was working in the home, the children would wake upwards at 6am on weekdays to take their showers and get dressed. So some of the children would make the beds while others helped to set the breakfast table or do some household chores. We would all have breakfast together and afterwards we'd give travel coin to the children who had to take the jitney to schoolhouse. The children who didn't leave for school would help finish the housework and and so there would be activities, such every bit football game or cartoon or homework time. In the evening, afterward dinner, we would watch Television receiver for a while and then the children would retire to read in their beds before going to sleep quite early. The weekends would be total of activities. From time to fourth dimension, at that place were volunteers who would take the children to run into movies. Each counselor had a diary in which he or she would write down what the children did in the home, with whom, and what his or her goals and dreams were, as well as what needed to be washed to fulfill those goals and dreams.

The home's overarching goal is to offering a good for you, safe environs and to foster the children's self-esteem, trust and sense of responsibleness.

Once each child becomes more than responsible, we allow him or her more than autonomy. But if a child gets involved in drugs over again, that child has to leave the middle.

W4: You lot say the child educators or counselors become into the streets to find the children and persuade them to join the home, but is at that place some choice made beforehand? Does any child who wishes to exit a life on the streets have access to Casa Alianza?

Sabrina Meder: Whatsoever child tin can enter the dwelling house; there'south no choice or selection made ahead of fourth dimension. A child first comes to Casa Alianza with the help of the counselors and educators, but the residual happens thanks to his or her own efforts and progress (which is monitored by counselors). In my case, I tried to show the children that they had real alternatives to their erstwhile lives. The children who spend fourth dimension at Casa Alianza often come from difficult family situations. For example, the father might be an alcoholic, the female parent might be a prostitute, or there might exist a family unit background of incest. Their babyhood contexts can be extremely tough. I tried to explicate to the children that they had options, that there were other genuine and viable possibilities in life. That'south how we managed to convince them to come to the home and at least effort out the experience of living there.

Sabrina Meder: Whatsoever child tin can enter the dwelling house; there'south no choice or selection made ahead of fourth dimension. A child first comes to Casa Alianza with the help of the counselors and educators, but the residual happens thanks to his or her own efforts and progress (which is monitored by counselors). In my case, I tried to show the children that they had real alternatives to their erstwhile lives. The children who spend fourth dimension at Casa Alianza often come from difficult family situations. For example, the father might be an alcoholic, the female parent might be a prostitute, or there might exist a family unit background of incest. Their babyhood contexts can be extremely tough. I tried to explicate to the children that they had options, that there were other genuine and viable possibilities in life. That'south how we managed to convince them to come to the home and at least effort out the experience of living there.

In one case, I went downwardly to the railways where there was a tiny, makeshift home. I constitute a child there. I can't retrieve his exact historic period, but he was a very little boy, perhaps 3 or four years erstwhile. He knew how to walk. His parents had totally neglected him–I retrieve that the child'southward articulatio genus was badly injured, just the parents hadn't done anything most it, they were completely drugged upwards. I felt powerless considering, of course, nosotros can't simply take a child away from his or her parents. But I tried to speak with the child, to condolement him, and I tried to advise and help the parents.

W4: During your stay at 1 of these transitional homes, you developed a couple of creative workshops to entertain the children and encourage them to express themselves. How did these workshops go? And why do yous prioritize art workshops specifically?

Sabrina Meder: I studied literature and I really love art, then artistic workshops were a natural choice for me. During my workshops, I would read a story to the children and inquire them to use the story as inspiration to create something of their ain. Those children who knew how to write and enjoyed writing would write something and the other children would draw. The results were surprising and impressive.

W4: Why surprising?

Sabrina Meder: The writing was stunningly symptomatic of the children's experiences. You could immediately tell that the stories were written by street children. For example, i child wrote, "Y'all shouldn't be a thief, considering it causes a lot of pain". The drawings and stories revealed the children'due south experiences and the impact of their experiences on their perception of the world – and that was fascinating.

I remember one story past a immature male child whose mother had died and whose father totally neglected him. His story demonstrated how conscious he was of how his groundwork and circumstances had limited his opportunities in life. It was astonishing to encounter a 15-twelvemonth-erstwhile with such an acute awareness of social problems and how such issues could limit the capabilities of children.

In that location were a couple of children who had lived in the sewers. I of them wrote a tale about a duck that never left the river because information technology was its home. And so the duck met a king of beasts who never left its den. The duck asked the lion why it never left its den. The lion responded that it was because it was afraid of being defenseless by hunters. The hunter represented the potential harm in life in the outside world. Information technology'due south noticeable that, whereas most children generally believe they are good, street children accept a dual self-perception: both positive and painfully negative, owing to the suffering they have endured.

In that location were a couple of children who had lived in the sewers. I of them wrote a tale about a duck that never left the river because information technology was its home. And so the duck met a king of beasts who never left its den. The duck asked the lion why it never left its den. The lion responded that it was because it was afraid of being defenseless by hunters. The hunter represented the potential harm in life in the outside world. Information technology'due south noticeable that, whereas most children generally believe they are good, street children accept a dual self-perception: both positive and painfully negative, owing to the suffering they have endured.

The children's drawings were also very revealing. For example, they tended to describe sad faces rather than the brilliant, smile faces that children usually produce. Or the children would depict crooked trees and a moon or a gray sun surrounded by lots of ominous clouds. Their drawings were elaborately symbolic, representing problems and threats, an unclear landscape, with colors depicting a melancholy, pitiful temper.

When I saw what the children produced, I wanted to compile their stories and drawings in order to give them a phonation and let them limited themselves to gild. In general, these children come from extremely underprivileged backgrounds, with no say in their lives and picayune voice in the world.

W4: In order to publish the piece of work, you had to participate in a competition to proceeds funding, which you lot won. Were people immediately interested in your project? What was your goal in publishing the book?

Sabrina Meder: Yes, people expressed involvement in the book; they plant the idea original. A one thousand copies were printed and they all sold out. I gave many public talks and presentations well-nigh the book, for example, at La Casa del Poeta (The Poet's Business firm) in Mexico, and also among my university students.

A foundation gave me effectually 36,000 pesos in social club to publish the book and I sold each re-create for twenty pesos, which wasn't expensive at all. In order to make a profit, I would have had to sell the book for ninety to 120 pesos, merely my goal wasn't to make money – I wanted the book to draw attending to street children'southward experiences and perspectives. To this end, I would sometimes requite the book abroad for free or donate copies to libraries.

A foundation gave me effectually 36,000 pesos in social club to publish the book and I sold each re-create for twenty pesos, which wasn't expensive at all. In order to make a profit, I would have had to sell the book for ninety to 120 pesos, merely my goal wasn't to make money – I wanted the book to draw attending to street children'southward experiences and perspectives. To this end, I would sometimes requite the book abroad for free or donate copies to libraries.

In Mexico, many people are so accustomed to poverty that, later a while, they don't even see it. I wanted to pause this bicycle of apathy and assist to render street children visible to society. It was hard at times because the street children didn't find information technology easy to trust people and often had difficulty opening up and expressing what they thought or felt. Only, looking back, I do feel that I've achieved my goal. Since the volume's publication, many articles on street children take been published in diverse newspapers and I've been able to raise sensation among my ain groups of students. Ultimately, I wanted these street children to be able to express themselves – and they've been able to exercise that.

For an first-class and unforgettable moving-picture show treatment of the effect of Mexico's street children, W4 recommends Eva Aridjis'southward prize-winning documentary, Ninos de la Calle (Children of the Street), which was made just over l years after the release of Luis Bunuel's searing 1951 masterpiece, Los Olvidados (The Forgotten Ones, also known as The Young and the Damned). Readers may also be interested in the powerful photographs of Kent Klich and in David Lida's panoramic delineation of gimmicky life in Mexico Urban center, First Cease in the New Earth: Mexico City, the Uppercase of the 21st Century (2009), which includes a short, brilliant affiliate on United mexican states's street children.

© Women's WorldWide Spider web 2012

Source: https://www.w4.org/en/wowwire/street-children-mexico-using-art-interview/

0 Response to "Drawing Like a Mexican the Childrens National Art Program Mexico"

Post a Comment