God the Father God the Father Seen in Art Panting

For about a grand years, in obedience to interpretations of specific Bible passages, pictorial depictions of God in Western Christianity had been avoided past Christian artists. At beginning but the Paw of God, often emerging from a cloud, was portrayed. Gradually, portrayals of the head and subsequently the whole figure were depicted, and by the time of the Renaissance artistic representations of God the Begetter were freely used in the Western Church building.[2]

God the Father tin be seen in some late Byzantine Cretan School icons, and ones from the borders of the Cosmic and Orthodox worlds, under Western influence, simply after the Russian Orthodox Church building came downward firmly confronting depicting him in 1667, he can hardly be seen in Russian fine art. Protestants generally disapprove of the depiction of God the Father, and originally did and so strongly.

Background and early history [edit]

Early Christians believed that the words of Book of Exodus 33:20 "1000 canst not see my face: for at that place shall no man see Me and live" and of the Gospel of John 1:18: "No man hath seen God at any time" were meant to apply not but to the Father, but to all attempts at the depiction of the Father.[3]

The Hand of God, an artistic metaphor, is establish several times in the only ancient synagogue with a big surviving decorative scheme, the Dura Europos Synagogue of the mid-3rd century, and was probably adopted into Early Christian art from Jewish art. Information technology was common in Late Antique art in both E and West, and remained the main way of depicting the deportment or approving of God the Father in the West until nigh the end of the Romanesque period. It besides represents the bathroom Kol (literally "girl of a vocalization") or vocalization of God,[4] similar to Jewish depictions.

Historically considered, God the Father is more often manifested in the Old Testament, while the Son is manifested in the New Testament. Hence it might be said that the Quondam Testament refers more particularly to the history of the Father and the New Attestation to that of the Son. Notwithstanding, in early depictions of scenes from the Old Testament, artists used the conventional delineation of Jesus to represent the Father,[5] particularly in depictions of the story of Adam and Eve, the nearly frequently depicted Old Testament narrative shown in Early Medieval art, and one that was felt to require the depiction of a effigy of God "walking in the garden" (Genesis iii:8).

The account in Genesis naturally credits the Creation to the single figure of God, in Christian terms, God the Father. Still the get-go person plural in Genesis one:26 "And God said, Let us make man in our prototype, after our likeness", and New Attestation references to Christ every bit Creator (John 1:iii, Colossians 1:15) led Early on Christian writers to associate the Creation with the Logos, or pre-existing Christ, God the Son. From the 4th century the church was as well keen to affirm the doctrine of consubstantiality confirmed in the Nicene Creed of 325.

Information technology was therefore usual to have depictions of Jesus every bit Logos taking the place of the Father and creating the earth solitary, or commanding Noah to construct the ark or speaking to Moses from the Called-for bush.[6] There was too a cursory flow in the 4th century when the Trinity were depicted as three about-identical figures, mostly in depicting scenes from Genesis; the Dogmatic Sarcophagus in the Vatican is the best known case. In isolated cases this iconography is constitute throughout the Heart Ages, and revived somewhat from the 15th century, though it attracted increasing disapproval from church authorities. A variant is Enguerrand Quarton's contract for the Coronation of the Virgin requiring him to represent the Father and Son of the Holy Trinity every bit identical figures.[seven]

I scholar has suggested that the enthroned effigy in the eye of the apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana in Rome of 390-420, normally regarded equally Christ, in fact represents God the Father.[8]

In situations, such as the Baptism of Christ, where a specific representation of God the Father was indicated, the Manus of God was used, with increasing liberty from the Carolingian period until the end of the Romanesque. This motif now, since the discovery of the 3rd-century Dura Europos synagogue, seems to have been borrowed from Jewish art, and is found in Christian art almost from its ancestry.

The use of religious images in full general continued to increase up to the end of the 7th century, to the point that in 695, upon assuming the throne, Byzantine emperor Justinian II put an paradigm of Christ on the obverse side of his gold coins, resulting in a rift which concluded the apply of Byzantine coin types in the Islamic world.[ix] However, the increase in religious imagery did not include depictions of God the Father. For example, while the eighty second canon of the Quango of Trullo in 692 did not specifically condemn images of The Father, it suggested that icons of Christ were preferred over Old Testament shadows and figures.[ten]

The beginning of the 8th century witnessed the suppression and destruction of religious icons as the period of Byzantine iconoclasm (literally image-breaking) started. Emperor Leo Three (717–741), suppressed the use of icons by majestic edict of the Byzantine Empire, presumably due to a military loss which he attributed to the undue veneration of icons.[11] The edict (which was issued without consulting the Church building) forbade the veneration of religious images merely did not utilize to other forms of art, including the image of the emperor, or religious symbols such every bit the cross.[12] Theological arguments confronting icons then began to announced with iconoclasts arguing that icons could not represent both the divine and the human natures of Jesus at the same fourth dimension. In this atmosphere, no public depictions of God the Father were even attempted and such depictions just began to appear ii centuries later.

The stop of iconoclasm [edit]

The Second Quango of Nicaea in 787 effectively ended the first period of Byzantine iconoclasm and restored the honouring of icons and holy images in general.[13] Withal, this did not immediately translate into big calibration depictions of God the Father. Even supporters of the use of icons in the 8th century, such equally Saint John of Damascus, drew a distinction betwixt images of God the Father and those of Christ.

In his treatise On the Divine Images John of Damascus wrote: "In former times, God who is without course or body, could never be depicted. But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I brand an image of the God whom I see".[14] The implication here is that insofar as God the Male parent or the Spirit did not become homo, visible and tangible, images and portrait icons tin can non exist depicted. So what was true for the whole Trinity earlier Christ remains true for the Father and the Spirit but not for the Word. John of Damascus wrote:[fifteen]

If nosotros attempt to make an paradigm of the invisible God, this would be sinful indeed. It is impossible to portray one who is without torso: invisible, uncircumscribed and without form.

Calvary hermitage, Alcora, Spain, 18th century.

Around 790 Charlemagne ordered a set of four books that became known as the Libri Carolini (i.e. "Charles' books") to abnegate what his court mistakenly understood to be the iconoclast decrees of the Byzantine 2d Council of Nicaea regarding sacred images. Although not well known during the Middle Ages, these books describe the key elements of the Cosmic theological position on sacred images. To the Western Church, images were just objects made by craftsmen, to exist utilized for stimulating the senses of the true-blue, and to exist respected for the sake of the subject represented, not in themselves.

The Council of Constantinople (869) (considered ecumenical by the Western Church, but not the Eastern Church) reaffirmed the decisions of the Second Quango of Nicaea and helped postage stamp out any remaining coals of iconoclasm. Specifically, its third canon required the image of Christ to have veneration equal with that of a Gospel book:[16]

We decree that the sacred image of our Lord Jesus Christ, the liberator and Savior of all people, must be venerated with the same honor as is given the book of the holy Gospels. For equally through the language of the words contained in this book all can reach salvation, so, due to the action which these images exercise by their colors, all wise and simple akin, tin can derive turn a profit from them.

Simply images of God the Father were not directly addressed in Constantinople in 869. A list of permitted icons was enumerated at this Council, just images of God the Male parent were not amid them.[17] All the same, the full general credence of icons and holy images began to create an atmosphere in which God the Father could exist depicted.[ citation needed ]

Middle ages to the Renaissance [edit]

God the Father with His Right Mitt Raised in Approving, with a triangular halo representing the Trinity, Girolamo dai Libri c. 1555.

Prior to the tenth century no attempt was made to represent a separate depiction as a total human figure of God the Father in Western art.[3] Yet, Western art eventually required some fashion to illustrate the presence of the Father, so through successive representations a set of artistic styles for the depiction of the Begetter in human form gradually emerged around the 10th century AD.

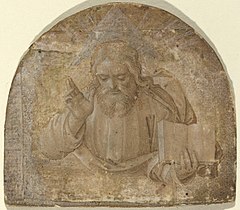

Information technology appears that when early artists designed to represent God the Father, fear and awe restrained them from a delineation of the whole person. Typically just a pocket-size part would be represented, usually the hand, or sometimes the face up, but rarely the whole person. In many images, the effigy of the Son supplants the Father, so a smaller portion of the person of the Father is depicted.[18]

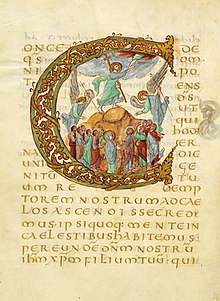

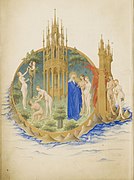

By the 12th century depictions of God the Father had started to appear in French illuminated manuscripts, which as a less public form could often exist more adventurous in their iconography, and in stained glass church windows in England. Initially the head or bosom was usually shown in some form of frame of clouds in the top of the picture space, where the Manus of God had formerly appeared; the Baptism of Christ on the famous baptismal font in Liège of Rainer of Huy is an example from 1118 (a Hand of God is used in another scene). Gradually the amount of the torso shown tin can increase to a half-length effigy, then a full-length, normally enthroned, as in Giotto'due south fresco of c. 1305 in Padua.[19] In the 14th century the Naples Bible carried a delineation of God the Father in the Burning bush. Past the early 15th century, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry has a considerable number of images, including an elderly just tall and elegant full-length figure walking in the Garden of Eden (gallery), which show a considerable diversity of credible ages and dress. The "Gates of Paradise" of the Florence Baptistry by Lorenzo Ghiberti, begun in 1425 show a similar tall full-length Father. The Rohan Volume of Hours of about 1430 also included depictions of God the Father in half-length man form, which were at present condign standard, and the Mitt of God condign rarer. At the same period other works, like the large Genesis altarpiece past the Hamburg painter Meister Bertram, continued to utilize the sometime depiction of Christ as Logos in Genesis scenes. In the 15th century there was a cursory fashion for depicting all 3 persons of the Trinity equally similar or identical figures with the usual appearance of Christ.

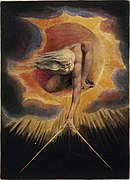

The Aboriginal of Days, a 14th-century fresco from Ubisi, Georgia.

In an early on Venetian schoolhouse Coronation of the Virgin by Giovanni d'Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini, (c. 1443) (meet gallery below) the Father is shown in the representation consistently used by other artists later, namely as a patriarch, with beneficial, nonetheless powerful eyebrow and with long white hair and a beard, a depiction largely derived from, and justified by, the clarification of the Ancient of Days in the Old Testament, the nearest approach to a physical description of God in the Old Testament:[20]

. ...the Ancient of Days did sit down, whose garment was white as snow, and the pilus of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the peppery flame, and his wheels as burning fire. (Daniel 7:9)

In the Declaration by Benvenuto di Giovanni in 1470, God the Father is portrayed in the red robe and a hat that resembles that of a Cardinal. However, even in the later part of the 15th century, the representation of the Father and the Holy Spirit as "hands and dove" connected, e.g. in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ in 1472.[21]

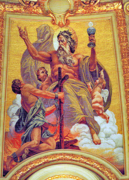

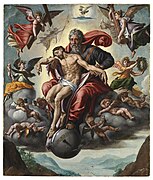

In Renaissance paintings of the admiration of the Trinity, God may exist depicted in two means, either with emphasis on The Father, or the three elements of the Trinity. The most usual delineation of the Trinity in Renaissance art depicts God the Father equally an old man, usually with a long beard and patriarchal in advent, sometimes with a triangular halo (equally a reference to the Trinity), or with a papal tiara, specially in Northern Renaissance painting. In these depictions The Begetter may hold a globe or volume. He is behind and above Christ on the Cross in the Throne of Mercy iconography. A dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit may hover above. Diverse people from dissimilar classes of order, due east.g. kings, popes or martyrs may exist present in the picture. In a Trinitarian Pietà, God the Begetter is often shown wearing a papal wearing apparel and a papal tiara, supporting the dead Christ in his artillery. They float in heaven with angels who carry the instruments of the Passion.[22]

The orb, or the world of the world, is rarely shown with the other two persons of the Trinity and is almost exclusively restricted to God the Begetter, merely is not a definite indicator since it is sometimes used in depictions of Christ. A book, although often depicted with the Father is not an indicator of the Father and is also used with Christ.[i]

From Renaissance to Baroque [edit]

Representations of God the Father and the Trinity were attacked both past Protestants and within Catholicism, by the Jansenist and Baianist movements as well as more orthodox theologians. As with other attacks on Cosmic imagery, this had the issue both of reducing Church building support for the less primal depictions, and strengthening it for the core ones. In the Western Church, the pressure to restrain religious imagery resulted in the highly influential decrees of the last session of the Quango of Trent in 1563. The Council of Trent decrees confirmed the traditional Catholic doctrine that images merely represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person, non the image.[23]

Artistic depictions of God the Male parent were uncontroversial in Cosmic art thereafter, only less mutual depictions of the Trinity were condemned. In 1745 Pope Bridegroom Fourteen explicitly supported the Throne of Mercy depiction, referring to the "Aboriginal of Days", simply in 1786 information technology was still necessary for Pope Pius 6 to upshot a papal balderdash condemning the decision of an Italian church council to remove all images of the Trinity from churches.[24]

God the Father appears in several Genesis scenes in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, most famously The Creation of Adam. God the Male parent is depicted equally a powerful figure, floating in the clouds in Titian's Supposition of the Virgin (see gallery below) in the Frari of Venice, long admired as a masterpiece of High Renaissance art.[25] The Church of the Gesù in Rome includes a number of 16th-century depictions of God the Father. In some of these paintings the Trinity is still alluded to in terms of iii angels, simply Giovanni Battista Fiammeri too depicted God the Father riding on a cloud, higher up the scenes.[26]

In both the Last Judgment and the Coronation of the Virgin paintings by Rubens (come across gallery below) he depicted God the Father in the form that by and so had go widely accustomed, as a bearded patriarchal figure in a higher place the fray. In the 17th century, the 2 Spanish artists Velázquez (whose father-in-law Francisco Pacheco was in accuse of the blessing of new images for the Inquisition) and Murillo both depicted God the Male parent every bit a patriarchal figure with a white bristles (meet gallery beneath) in a majestic robe.

While representations of God the Father were growing in Italia, Spain, Deutschland and the Low Countries, there was resistance elsewhere in Europe, even during the 17th century. In 1632 most members of the Star Chamber court in England (except the Archbishop of York) condemned the use of the images of the Trinity in church windows, and some considered them illegal.[27] Subsequently in the 17th century Sir Thomas Browne wrote that he considered the depiction of God the Male parent every bit an old man "a dangerous act" that might pb to Egyptian symbolism.[28] In 1847, Charles Winston was still critical of such images as a "Romish trend" (a term used to refer to Roman Catholics) that he considered all-time avoided in England.[29]

In 1667 the 43rd chapter of the Peachy Moscow Quango specifically included a ban on a number of depictions of God the Father and the Holy Spirit, which and so also resulted in a whole range of other icons beingness placed on the forbidden list,[xxx] [31] more often than not affecting Western-manner depictions which had been gaining ground in Orthodox icons. The Council also alleged that the person of the Trinity who was the "Ancient of Days" was Christ, as Logos, non God the Father. However some icons continued to exist produced in Russia, likewise as Hellenic republic, Romania, and other Orthodox countries.

Gallery of art [edit]

15th century [edit]

16th century [edit]

17th century [edit]

-

Rubens Last Judgment (detail) 1617

-

Crowning of the Virgin by Rubens, early 17th century

-

-

-

18th-20th centuries [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Offset Vision, 1913, with God the Male parent on the right, and Jesus Christ on the left.

-

Come across also [edit]

- Holy Spirit in Christian art

- Trinity in Christian art

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b George Ferguson, 1996 Signs & symbols in Christian art ISBN 0-19-501432-4 page 222

- ^ George Ferguson, 1996 Signs & symbols in Christian fine art, ISBN 0-19-501432-4 page 92

- ^ a b James Cornwell, 2009 Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art ISBN 0-8192-2345-X page two

- ^ A affair disputed by some scholars

- ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron, 2003 Christian iconography: or The history of Christian art in the middle ages, Book 1 ISBN 0-7661-4075-10 pages 167

- ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron, 2003 Christian iconography: or The history of Christian fine art in the middle ages, Book one ISBN 0-7661-4075-X pages 167-170

- ^ Dominique Thiébaut: "Enguerrand Quarton", Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2007, [i]

- ^ Suggestion by F.West. Sclatter, see review by W. Eugene Kleinbauer of The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Fine art, by Thomas F. Mathews, Speculum, Vol. lxx, No. four (October., 1995), pp. 937-941, Medieval Academy of America, JSTOR

- ^ Robin Cormack, 1985 Writing in Gold, Byzantine Lodge and its Icons, ISBN 0-540-01085-5

- ^ Steven Bigham, 1995 Prototype of God the Male parent in Orthodox Theology and Iconography ISBN ane-879038-15-3 page 27

- ^ According to accounts by Patriarch Nikephoros and the chronicler Theophanes

- ^ Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine Country and Lodge, Stanford University Printing, 1997

- ^ Edward Gibbon, 1995 The Decline and Autumn of the Roman Empire ISBN 0-679-60148-1 folio 1693

- ^ St. John of Damascus, Iii Treatises on the Divine Images ISBN 0-88141-245-vii

- ^ Steven Bigham, 1995 Image of God the Father in Orthodox Theology and Iconography ISBN one-879038-xv-3 folio 29

- ^ Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen, 2005 Theological aesthetics ISBN 0-8028-2888-four page 65

- ^ Steven Bigham, 1995 Image of God the Male parent in Orthodox Theology and Iconography ISBN 1-879038-fifteen-3 page 41

- ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron, 2003 Christian iconography: or The history of Christian fine art in the center ages ISBN 0-7661-4075-X pages 169

- ^ Arena Chapel, at the height of the triumphal arch, God sending out the angel of the Annunciation. Encounter Schiller, I, fig 15

- ^ Bigham Affiliate 7

- ^ Arthur de Bles, 2004 How to Distinguish the Saints in Art by Their Costumes, Symbols and Attributes ISBN 1-4179-0870-X page 32

- ^ Irene Earls, 1987 Renaissance art: a topical lexicon ISBN 0-313-24658-0 pages viii and 283

- ^ Text of the 25th decree of the Council of Trent

- ^ Bigham, 73-76

- ^ Louis Lohr Martz, 1991 From Renaissance to bizarre: essays on literature and art ISBN 0-8262-0796-0 page 222

- ^ Gauvin A. Bailey, 2003 Between Renaissance and Baroque: Jesuit art in Rome ISBN 0-8020-3721-6 page 233

- ^ Charles Winston, 1847 An Enquiry Into the Divergence of Style Appreciable in Ancient Glass Paintings, Specially in England ISBN 1-103-66622-three, (2009) folio 229

- ^ Sir Thomas Browne'due south Works, 1852, ISBN 0559376871, 2006 page 156

- ^ Charles Winston, 1847 An Inquiry Into the Difference of Fashion Observable in Aboriginal Glass Paintings, Especially in England ISBN 1-103-66622-3, (2009) page 230

- ^ Oleg Tarasov, 2004 Icon and devotion: sacred spaces in Imperial Russia ISBN 1-86189-118-0 folio 185

- ^ Orthodox church web site

Farther reading [edit]

- Manuth, Volker. "Denomination and Iconography: The Pick of Bailiwick Matter in the Biblical Painting of the Rembrandt Circle", Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 22, no. four, 1993, pp. 235–252., JSTOR

External links [edit]

- Age of spirituality : late antiquarian and early on Christian fine art, 3rd to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/God_the_Father_in_Western_art

0 Response to "God the Father God the Father Seen in Art Panting"

Post a Comment